Introduction

In late October, 2014, demonstrations started to be held in Budapest, Hungary, which were triggered by the government’s announcement of a proposal about an Internet tax to be entered in 2015. The ruling right-wing coalition’s larger party, the conservative Fidesz made their proposal public on October 21, as part of the modified “Taxation Law” meant to extend the existing telecommunications tax to Internet usage. The proposal designates a 150 forint/GB tax rate (with 150 forint being around 62 US cent, 38 British penny and 49 eurocent). This idea, possibly coupled with other current issues surfacing around the government prompted multiple, generally peaceful demonstrations in Budapest and in other cities in and outside Hungary.

![]()

A Facebook page named Százezren az internetadó ellen (“Hundred Thousand Against the Internet Tax”) was created on the same day the proposal was made public by Balázs Gulyás, a 27 year old political blogger. A week later, on the 28th, the page had more than 225,000 likes.

![]()

Gulyás acted as the main organizer of the two Budapest demonstrations, also making speeches to the crowd. The first event was on the 26th in the early evening hours, and instantly got international media coverage. According to mainstream news portals, tens of thousands of people gathered, and while the demonstration’s intention was peaceful, hundreds of people attacked the Fidesz party headquarters after the event finished. The building’s fence was toppled and its windows were broken in, many people hurled broken computer equipment at the building, including monitors. The day ended with no riot police intervention, though they were assigned to the scene after some time.

![]()

Despite the demand of the demonstrators, Fidesz made it clear they will enter the new tax next year, but they proposed an amendment to cap the tax at 700 forint/month/subscriber for home users and 5000 forint/month/subscriber for business users, while stating they intend the tax to be paid by the ISPs rather than the end users. The demonstrators, not finding this satisfactory, gave an “ultimatum” to the government to abandon the plan in the next 48 hours or they would face another mass demonstration. Since Fidesz didn’t retract their idea, another demonstration was held on the 28th in the early evening hours. Simultaneously, similar events took place in multiple cities in Hungary, and also in Warsaw, Poland. All these later events ended without any vandalism, although riot police was guarding the Parliament building. Reuters estimated the number of people around 100,000 at the second Budapest demonstration, which was concluded with Gulyás saying that “this is only the beginning”, and projected another gathering for November 17, the day the parliament will vote on the modified Tax Law.

![]()

Background

Some media outlets speculated about the possible reasons behind the fact that the demonstrations are the largest anti-government events since the protests in 2006 against then-ruling socialist party MSZP. Fidesz won the elections in 2010 with a large majority, making them being able to pass laws without hindrance from other political forces, and they also won the 2014 election. Party chairman and prime minister Viktor Orbán used this political power to introduce several changes according to his political visions, like opening towards Eastern nations outside the European Union, notably Russia. Fidesz also crafted the new constitution of Hungary on the basis that the existing one existed as a legacy of the fall of communism 1989.

![]()

Possible reasons for the demonstrations’ popularity include Fidesz’s austerity measures and new taxes affecting the telecommunication, energy, and banking sectors, the dissolution of the private pension fund system, the adoption of a new constitution crafted solely by Fidesz, the approval of the new “Media Law”, the decision accepting a Russian loan to support the expansion of the Paks Nuclear Power Plant, and the supposedly shady nationalization of tobacco shops. Two focal issues which demonstrators are well aware of are the corruption accusations of government-related officials by the US government, and the fact that Fidesz itself opposed and criticized a similar Internet tax when rival MSZP considered it in 2008.

Online reactions

On Twitter, multiple hashtags became associated with the tax and the demonstrations, the most widely used is #internetado (“Internet tax”). Others include #netado (“net tax”) and #internettax.

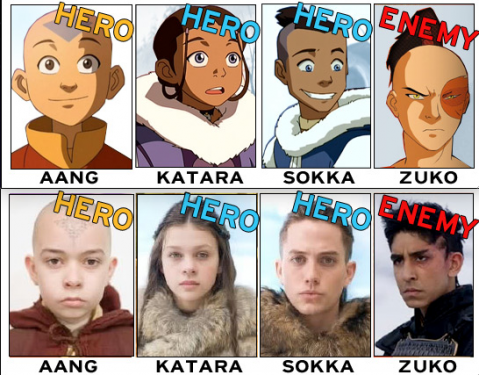

The Százezren az internetadó ellen page and other online forums received images which mocks and ridicules Fidesz and the idea of the Internet tax, generally by using an already established meme, but sometimes with sarcastic photoshops. In contrast to this, some images poked fun at the fact that people decided to go out protesting only when an Internet tax was considered by the government which they dislike.

Notable examples of memetic reactions

Search interest

External references